KOOKLE/Shutterstock

Vivian Hoffmann, The International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI)

An exposé in Kenya has revealed that there are high amounts of a poisonous substance, known as aflatoxin, in many of Kenya’s popular maize flour brands. This is particularly worrying as maize flour is a staple food for most Kenyans. Part of the problem is in how maize is processed and distributed in the country. Vivian Hoffmann shares her insights on this and what must be done to prevent it.

What are aflatoxins and how do they get into our food?

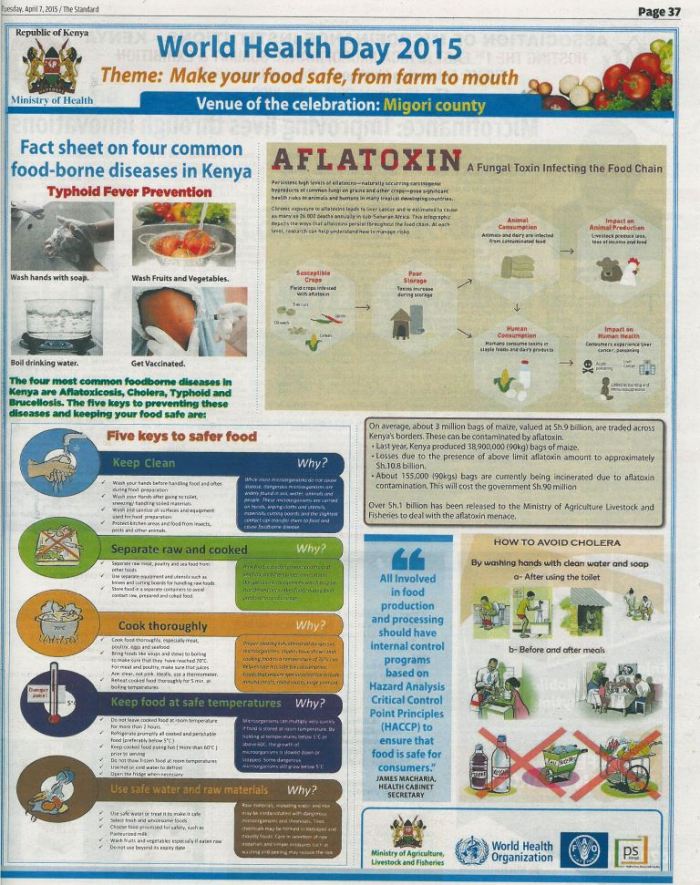

Aflatoxins are toxic chemicals produced by a fungus, Aspergillus flavus. The fungus occurs naturally in soils, but under hot, dry conditions, it can grow and spread to a variety of crops. Maize and groundnut are two crops that are especially susceptible to contamination with aflatoxins.

While aflatoxin is a known carcinogen, and can be fatal to people in large doses, some of the other potential health impacts of consuming moderate amounts of aflatoxin over long periods of time are less well understood.

The amount of harvest that’s affected by aflatoxins varies each year, depending on the weather. Either too little rain during cultivation (which weakens the crops’ natural defences against fungal infection), or too much around harvest (which makes it difficult to dry the crops before storage), can lead to higher aflatoxin.

Poor plant nutrition is also a risk factor because, like drought conditions, it weakens crops and makes then susceptible to being colonised by fungus.

The fungus can continue to grow on crops if they’re not properly stored (and moisture gets in), or if they’re not well dried. In Kenya, maize stored by smallholder farmers has been found to be far more contaminated than purchased maize and is the most likely culprit for the outbreaks of aflatoxin poisoning that occur from time to time.

It’s not a uniquely Kenyan challenge. Aflatoxin contamination occurs in almost all countries. A non-exhaustive list of other aflatoxin hotspots includes the Southern US, Guatemala, parts of China, and India.

What is being done to try to address this issue and what’s not working

In Kenya, many food processing companies test inputs – like maize – before buying to avoid aflatoxin contamination in their products. But accurate testing is difficult because there is a lot of variation in aflatoxin across bags of maize, and even grains within a bag.

Under Kenyan law, maize that contains more than 10 parts per billion total aflatoxins, and groundnut above 15 parts per billion aflatoxin, cannot legally be sold. But testing procedures are not regulated.

On top of this, testing for aflatoxin at the factory gate doesn’t really solve the problem. When a consignment of maize or groundnut is rejected by one company, it is simply sold to a company with less stringent requirements, or on the informal market. This means the lowest-cost food is often the most contaminated, and people with the least to spend are at greatest risk of eating unsafe food.

In my ongoing research, I’ve found that a great deal of maize consumed in Kenya is never even tested for aflatoxin. This is because it’s either bought on the informal market, or consumed by those who have grown it.

Are there any steps that the public can take to avoid consuming them?

The International Food Policy Research Institute’s research on maize flour in Kenya has shown that more expensive brands are more likely to be compliant with the aflatoxin standard. Buying higher-priced maize flour is one way to protect yourself.

Also, if you grow your own maize or groundnut, dry your crops thoroughly while preventing contact with the soil, and store them in a clean, dry place.

Processed foods containing groundnut (also known as peanut) are usually more contaminated than whole nuts. This is probably because visibly damaged nuts are more likely to contain aflatoxin, and the best nuts are sold whole rather than processed. Grinding your own peanut butter from high-quality nuts is one way to avoid aflatoxin in this food.

Finally, one of the most important things you can do to avoid aflatoxin is to eat a balanced diet and avoid over-reliance on maize and groundnut.

What needs to happen next?

More resources are needed to deal with aflatoxin contamination at its root, which is on the farm.

The Kenyan government recently announced plans to spend Ksh 200 million on Aflasafe, an aflatoxin-control product that farmers apply to crops while they are still in the field. This is excellent news, but it’s extremely important that farmers are trained on how to correctly apply it for the treatment to be effective.

Other practices, including drying crops on plastic sheets, removing visibly mouldy or damaged crops prior to storage, and storing well-dried crops in hermetic bags, are also very effective at reducing aflatoxin. Plastic sheeting is available for around 400 KSh (about US$4) for a 15m2 piece, and can last multiple seasons, making it one of the most cost-effective solutions available.

There also needs to be a change in Kenya’s aflatoxin regulation to legalise the use of contaminated grain for specific non-food uses. The East African Standard for maize, which Kenya follows, requires all maize to meet the same aflatoxin limit, regardless of its use.

Since very little aflatoxin passes from feed into meat, crops that are considered unsafe for human consumption can be safely used as feed for animals to be slaughtered for meat. Many countries, including the US and EU members, allow higher levels – up to 30 times the Kenyan limit – in feed consumed by meat animals. Allowing food that exceeds the aflatoxin limit for human consumption to be fed to meat animals is a way to get this poison out of the food supply.![]()

Vivian Hoffmann, Research economist, The International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI)

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.